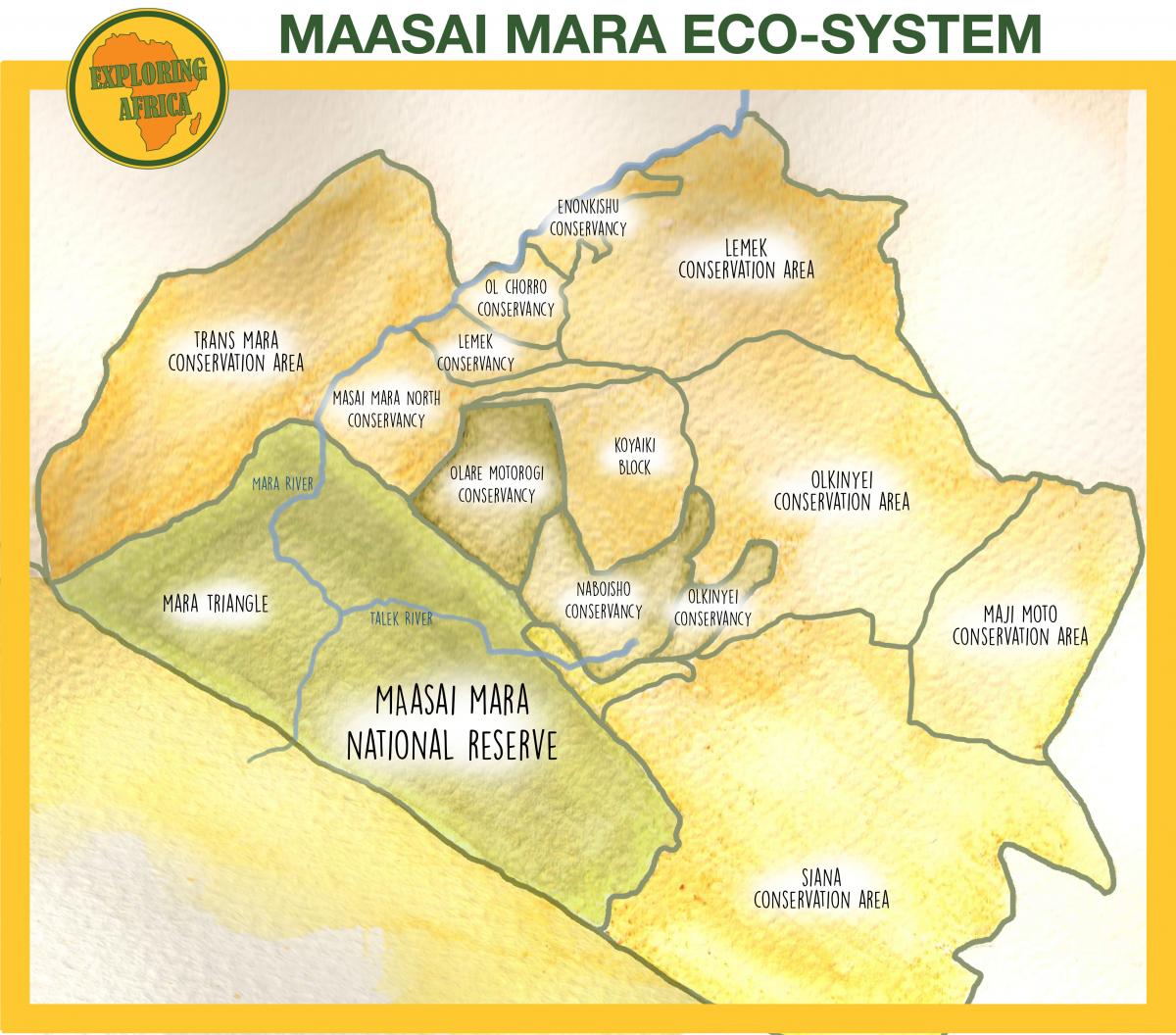

The Great Migration is one of the most exciting and amazing events in the world: two million wildebeests and zebras, the number changes every year, run along an 800 km circular route across the plains of the Serengeti National Park, the Ngorongoro Conservation Area and Maswa Reserves, the Grumeti and Loliondo in Tanzania and in the grasslands of the Masai Mara National Reserve and neighbouring Conservancies.

A restless journey within the Serengeti Ecosystem, punctuated by the alternation of seasons and moved by the constant search of water and fresh pastures; a path that has remained unchanged over centuries and millennia, that is witnessed by the petroglyphs depicting the herds of the Great Migration in the Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania.

The herds start to climb Northwards in May and they usually reach the Masai Mara National Reserve in Kenya in early July, but it may happen that they anticipate their arrival due to changing weather conditions.

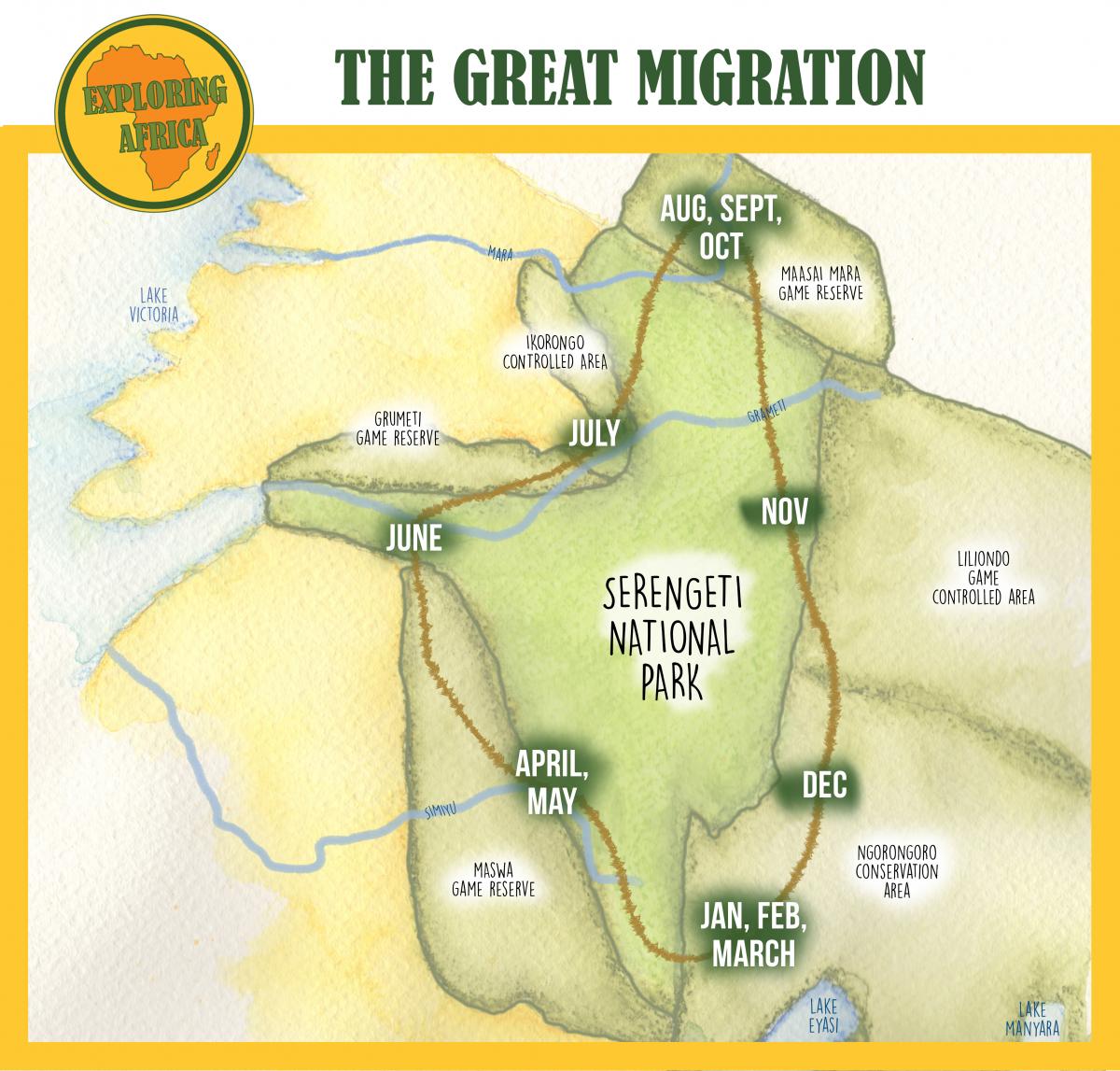

The driving forces are their dependence on water and the need for new pastures; only in this part of the Serengeti Ecosystem there are large perennial rivers that ensure the survival of the species during the long dry season; especially the Mara River, running through the Masai Mara National Reserve and the neighbouring private reserves in Kenya, and then flowing Southwards in Tanzania, through the Serengeti National Park, into Lake Victoria.

If you visit the Masai Mara National Reserve in the months of the Great Migration you can enjoy this marvel of nature in the forefront and view, with a bit of luck, the crossing of the Mara River.

The herds reach Kenya from different access points.

Most of them come to Kenya after crossing the Mara River on the Western side of the Masai Mara National Reserve, i.e. the Mara Triangle; from here they point Eastwards, by crossing the Mara River again and reaching the Musiara and Sekenani regions; others continue their journey Northwards to the Conservancies.

Other herds instead enter the Masai Mara National Reserve in the Sekenani sector, by crossing the shallow Sank river, a tributary of the Mara River; then they turn West and cross either the Talek or the Mara rivers, that have a higher water flow; from here some of them point Northwards and enter the Conservancy area, others stop in the National Reserve.

During they stay here they continue to move from one point to another, crossing and re-crossing the river, looking for new pastures.

The crossing of these often impetuous rivers is the most dangerous event of the migration cycle; in this time of the year the waters flow fast, especially those of the Mara river, that, after the heavy rainfalls on the Mau Escarpment, has its peak flow rate and the animals are likely to be dragged by the current; also on the river bed there are often large boulders that are a threat to be overlooked for the jumping wildebeests and zebras as they may break a leg on the uneven river bed.

What’s more, the river is infested with the Nile crocodiles that have awaited for months the return of the herds for an easy feast; sometimes the crocodiles only feed on the animals that are unfortunately drowned, sometimes they tend ambushes during the difficult crossing.

The ascent on the opposite bank of the river has no lack of pitfalls, either: predators, such as lions, hyenas, leopards, cheetahs, jackals and vultures, some of which follow the herds as they move around, stay lurking near the river and try to take advantage of the situation; they often catch specimens that were injured during the crossing or puppies that are the most vulnerable.

Viewing the crossing is an exciting event that is unbelievable and impossible to describe.

You can’t fail feeling a sort of anxiety and fear for the fate of the herds huddled on the river banks, with the most experienced species monitoring the river and its banks in search for the best point from where to cross and try to avoid all risks; when they seem to muster up boldness and start the crossing, you can’t but cheer for them, against everything and everyone, and you find yourself holding your breath and be concerned of their fate as they throw themselves from the high sandy bank into the river waters, where they jump heavily and try to reach the other bank, and finally you feel happy when they reach the opposing bank.

It is important to know that the herds do not cross the Mara river only once when they move Northwards and then back Southwards, but during the months they stay in this area, they cross several times the Mara and Talek rivers that flow in the Masai National Reserve in several places and in different directions.

This incessant movement is due to the fact that the herds consume the pastures at a higher rate than that with which the grass generates, so the animals are forced to move elsewhere looking for new sources of food, leaving time to pastures to regenerate.

In late October, when the first rains begin in the South, between late October and early November, the herds start to travel, leave the Masai Mara National Reserve and return to Tanzania; they will return the following year as it has been going on year after year.

The movement of the Great Migration across the Serengeti Ecosystem grasslands, overcoming obstacles and dangers, is the cycle of life and the struggle for survival; during their continued migrating, wildebeests and zebras overcome everyday pitfalls, mate, and every year the new-born puppies are immediately ready to join the march; even when they stop in an area for a few months, they continue to move from one place to another in search for food.

On their journey, wildebeests tend to form endless 30-40 km lines of dark animals marching orderly across the grassland that has become yellow due to the drought typical of the dry season or bright green in the rainy season, offering spectacular and exciting views.

There are neither precise routes or predetermined timing for migration, these herbivorous are driven by the instinct of survival and their movements depend on weather conditions; it seems that the more expert animals, that have already covered these routes several times, lead the herds, and once compacted, each of them confidently follows the one preceding it.

We know that not all specimens migrate, some remain throughout the year in the ecosystem of the Great Masai Mara, and likewise some remain in various parts of the Serengeti.

In particular, many do not know that, in addition to the famous Great Migration, another one takes place in the Great Masai Mara Ecosystem, the Loito Hills Migration.

As many as 250,000 wildebeests go down into the Masai Mara National Reserve in May or June, in conjunction with the arrival of the herds from the South, and stop here until November; with the beginning of the first rainfalls they return Northwards into the private reserves, namely the Mara North Conservancy, Naboisho Conservancy and Olare Motorogi Conservancy.

But sometimes, if there are only few short rains, the animals remain in the Masai Mara National Reserve until March or April, at the beginning of the heavy rain season.